Why the Fed’s Job May Get a Lot More Difficult

When inflation was too high and the economy was resilient in the aftermath of the pandemic, the Federal Reserve’s decision to sharply raise interest rates beginning in 2022 seemed like a no-brainer. The same was true just over two years later when inflation had fallen sharply from its recent peak and the labor market had started to cool off. That paved the way for the central bank to lower borrowing costs by a percentage point in 2024.

What made those decisions relatively straightforward was the fact that the Fed’s goals of achieving low and stable inflation and a healthy labor market were not in conflict with each other. Officials did not have to choose between safeguarding the economy by lowering rates and staving off price increases by either keeping rates high or raising them further.

Economists worry that could soon change. President Trump’s economic agenda of tariffs, spending cuts and mass deportations risks stoking inflation while simultaneously denting growth, an undesirable combination that could lead to much tougher trade-offs for the Fed.

“We’re getting to a harder decision point for the Fed,” said Nela Richardson, chief economist at ADP, the payroll processing company.

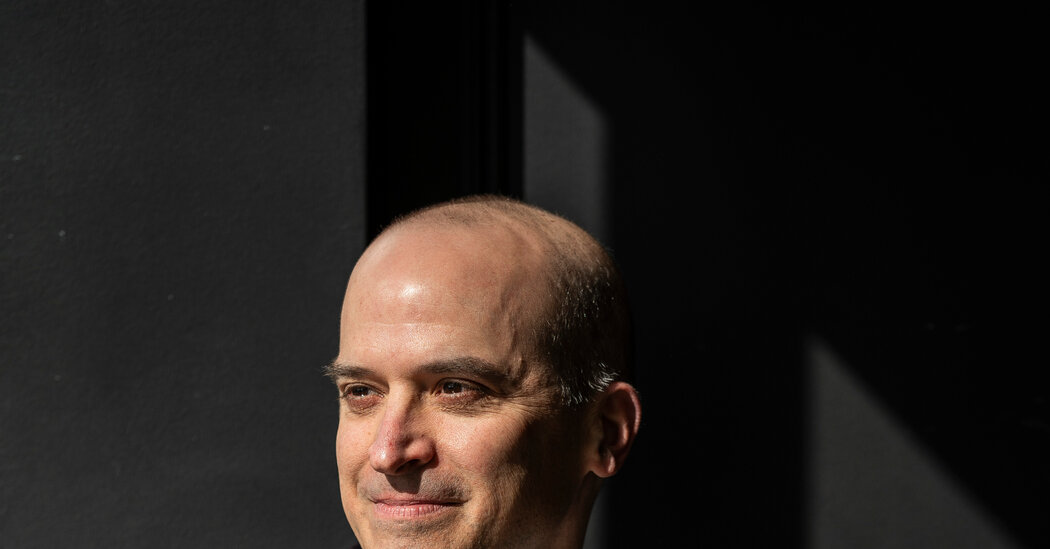

Jerome H. Powell, the Fed chair, indicated little concern about this dilemma on Wednesday after the Fed’s decision to keep interest rates unchanged for a second-straight meeting in light of a highly “uncertain” economic outlook.

Mr. Powell did warn that “further progress may be delayed” on getting inflation back to the central bank’s 2 percent target because of tariffs. A combination of rising inflation and weaker growth would be “a very challenging situation for any central bank,” he conceded, but it was not one the Fed currently found itself in.

“That’s not where the economy is at all,” Mr. Powell said during a news conference. “It’s also not where the forecast is.”

The United States is unlikely to find itself in a full-blown period of stagflation, in which inflation soars, growth contracts and unemployment spikes. But economists are not yet ready to dismiss the possibility that real tensions between the Fed’s goals could arise in the coming months given the extent of Mr. Trump’s plans.

“There is a risk that there is misplaced confidence around inflation,” said Michael Gapen, chief U.S. economist at Morgan Stanley. Mr. Powell came off as “very complacent,” he added.

During the news conference, the chair appeared unbothered by surging inflation expectations captured in a recent survey by the University of Michigan, which showed participants souring sharply on the outlook.

He also resurrected the notion that an inflation shock caused by supply-related issues like tariffs could indeed be “transitory.”

Tariffs, which are a tax on imports, are expected to raise costs for consumers. The question is whether those increases will feed into persistently higher inflation.

The word “transitory” gained notoriety after the Fed and other forecasters used it to initially describe price pressures that emerged after the pandemic. Those ended up being far more pernicious, leading to the worst inflation shock in decades.

New projections released by the Fed on Wednesday seemed to suggest officials were prepared to look through, or not react to, tariff-induced price pressures, which they saw lifting their preferred inflation measure — once food and energy prices are stripped out — to 2.8 percent by the end of the year. That would signify an acceleration from January’s 2.6 percent pace. By the end of 2026, they expect it will fall back to 2.2 percent.

Officials simultaneously marked down their forecasts for growth to 1.7 percent from 2.1 percent in December while raising those for unemployment to 4.4 percent, a backdrop they essentially expect to remain in place through 2027.

Despite these shifts, a majority of policymakers stuck with earlier estimates for a half a percentage point reduction in rates this year, or two more cuts. Another two are expected in 2026. Investors interpreted this to be an extremely dovish approach, fueling a rally in stock and government bond markets.

Giving some economists pause, however, is the significant uncertainty inherent not only in officials’ forecasts themselves, but also in the way Mr. Powell talked about the outlook.

Policymakers penciled in a far higher degree of uncertainty than they did in December and broadly saw bigger risks to their estimates for inflation, growth and unemployment, their projections showed. Rising uncertainty also made it into the Fed’s updated policy statement, and at one point during the news conference, Mr. Powell characterized it as “remarkably high.”

At one point when asked about officials’ rate forecasts, he quipped: “What would you write down? It’s really hard to know how this is going to work out.”

That uncertainty has raised questions about how much stock to put in the more benign scenario financial markets appear to be pinning their hopes on.

Tim Mahedy, who previously worked at the San Francisco Fed and is now chief economist at Access/Macro, a research firm, said the central bank’s most recent experience being “stung” by inflation and the fact that it had yet to be fully vanquished meant the bar for officials to respond to economic weakness was higher than otherwise would be the case.

“They’re going to be a little bit more tolerant of weakness in growth relative to an increase in inflation,” added Peter Hooper, who worked at the Fed for almost 30 years and is now vice-chair of research at Deutsche Bank. “They recognize that if they let inflation get away, that’s going to worsen the growth impact down the road and further limit their ability to offset it.”